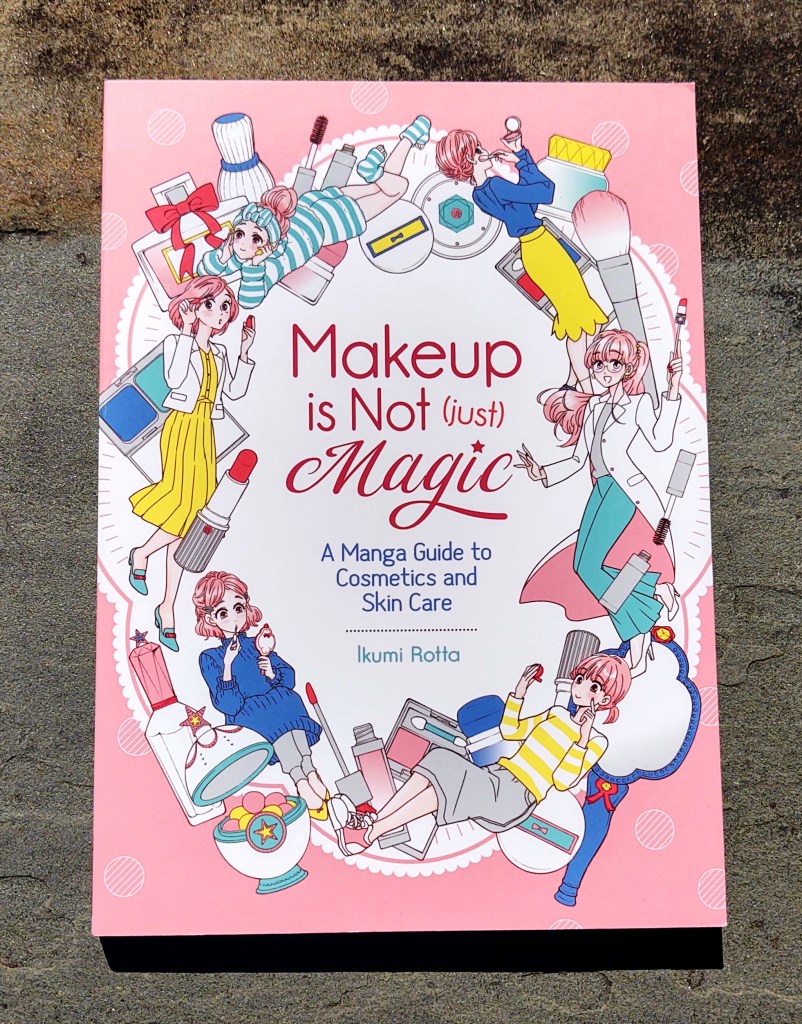

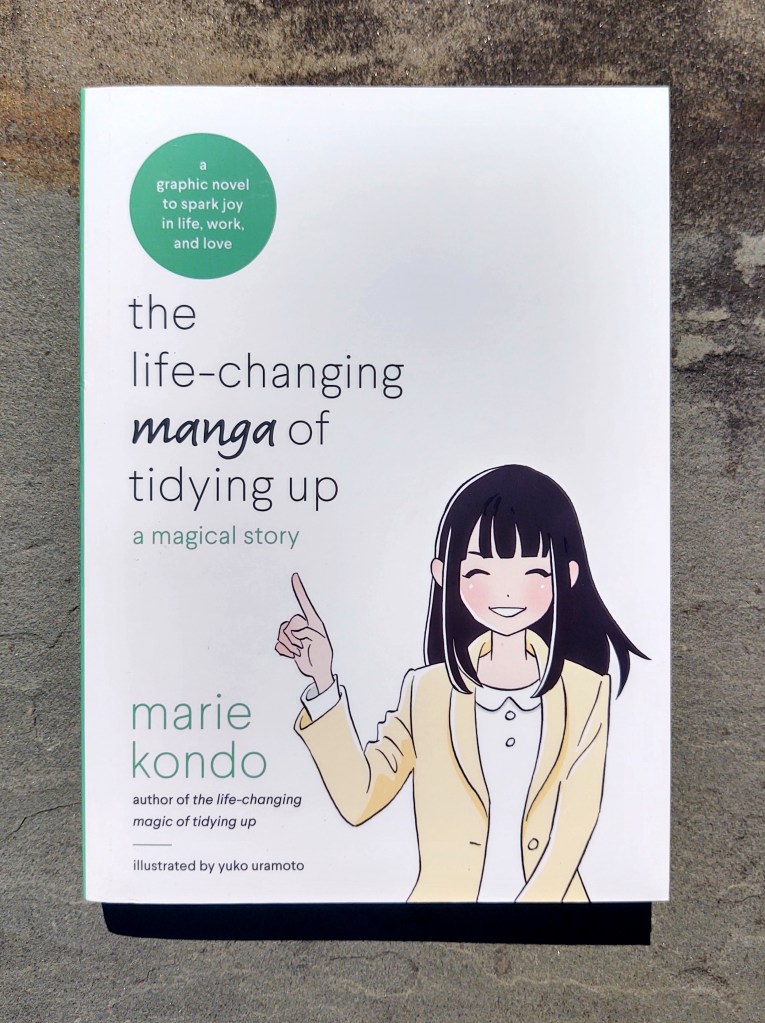

I bought Make-up is (Not) Magic: A Manga Guide to Cosmetics and Skin Care on release day for a few reasons. I appreciated the busy, pink josei cover. I wanted to instill some optimism within myself that I will soon secure a job where I can have disposable income to spend on fancy makeup. But most importantly, after loving The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up, the manga adaptation of Marie Kondo’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, I’ve become fascinated by how-to comics.

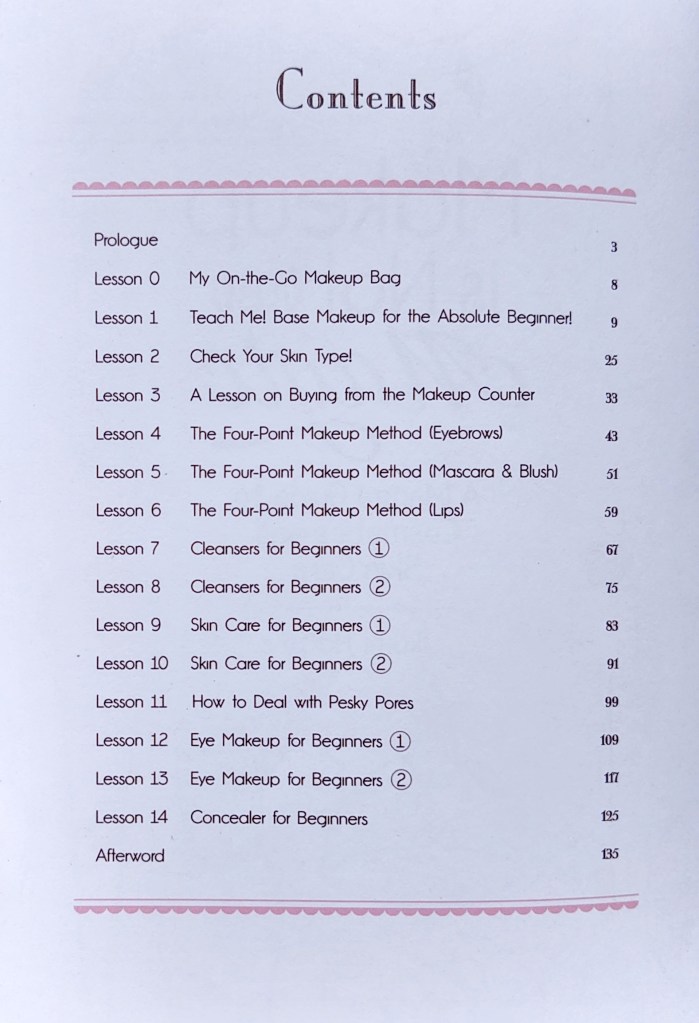

Creator Ikumi Rotta first started Makeup is Not (Just) Magic as a magazine column for intermediate makeup users. She later adapted it into a web series for makeup beginners, which was then complied into this book. For 135 pages, it covers a lot of ground.

The script is a piece of fiction. The instructor is shojo manga artist Rokka Narumi, Rotta’s “idealized” self that she “aspired to be as a beauty consultant.” Her pupils are fans submitting makeup questions over Twitter. But the fans’ reasons for reaching out usually amount to a simple, “I don’t know what to do.” There is very rarely a personalized reason (e.g. an allergy, a wedding, an aesthetic goal) motivating them to contact Rokka.

To be fair, the subject matter itself is a bit restrictive. Skin types are diverse, so giving a “one size fits all” answer to a personal question is impossible. Beauty and body image can also be sensitive issues. As a result, the “payoff” in Makeup is subtle. It’s limited to makeup newbies expressing surprise and enthusiasm about their look and pledging to continue practicing.

Without (even fictionalized) emotional or personal associations to specific pieces of advice, I found most of the tips on makeup application washing over me. The book felt more like a reference textbook –a tool for refreshing my memory or reviewing specific tasks – than an introductory guide.

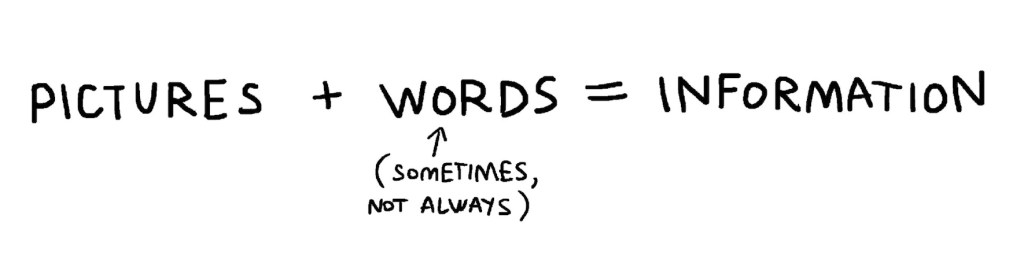

As I read Makeup, I couldn’t help but think of a tweet I saw some time ago about IKEA instructions. I managed to dig it up, and it turned out to be a quote from comics artist Maris Wicks in her presentation “Comics + Science: Using Cartoons to Communicate.” A little over five and half minutes in, Wicks condenses the definition of comics into to a simple equation:

She gets to the quote I was looking for a bit later:

And by my definition, an IKEA instruction is comics. Whether or not it’s effective as a way of communication is up for debate, but I would say that with this definition comics could possibly save your life or get you out of a pickle. I mean, there’s a reason why we use this method to communicate important information. I acknowledge that there are seven different languages on this airline card, but most of the important information is drawn using sequences of pictures with some iconography that we recognize, like the red circle with a line through it is pretty much universally ‘no’ or ‘don’t.

I happen to have an IKEA instruction manual laying around my apartment. It beats Wicks’ airline card with 36 languages used for the most important safety warnings. But I was really struck by two brief comics featured on the first page:

Both comics prompt the customer to action via emotional cues on the human figure’s face: Want to avoid disappointment? Build on a soft surface. Confused by these instructions? Call the store. What I find truly special about these two comics, though, is that they can also be read as short stories, each with a conflict and a resolution: They didn’t want to break their new furniture, so they built on a soft surface. They were confused, so they called the store.

Wicks emphasizes the power of story in communicating factual information. She does a reading of one of her comics where various sea creatures explain how their camouflage works. After the reading, Wicks admits:

I’m doing something kind of weird here. I’m presenting you with factual information, but I’m doing it in a fictional way. So I’m walking this tightrope where I’m bending the rules of nonfiction by giving a voice to things that don’t have voices. Or by giving a story to this information. And I think that’s the biggest part of why I do what I do. Because I don’t honestly care that those are three different methods of camouflage…The important part is why. Why is it there? What’s the story?

This big “Why?” is what made the manga adaptation of Marie Kondo’s book so effective.

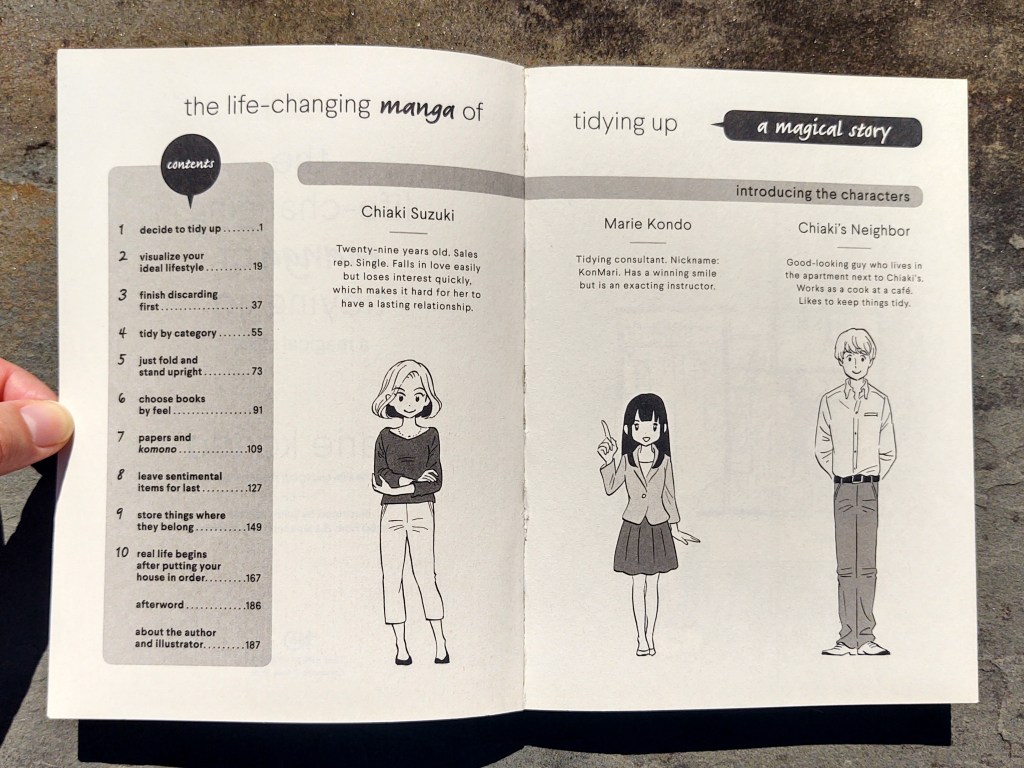

Note how the subtitle is “a magical story.” We are introduced to the “cast” of this story alongside the table of contents:

Before the story even starts, we can infer the main conflict from these character profiles. Chiaki is a busy working woman (i.e., doesn’t have time to clean). She is a romantic and has noticed her cute neighbor, but their lifestyles clash. Tidying guru Marie Kondo’s life lessons are presented within the context of this fictional conflict.

Kondo shows up at Chiaki’s apartment like a fairy godmother (literally, Chiaki is surprised by Kondo’s stature and thinks, “She looks more like a fairy!”) and structures her entire cleaning lesson around Chiaki’s long-term goals. Her first “cleaning” assignment for Chiaki is to think about what life changes she wants to achieve by tidying her apartment. To verbalize these changes, Chiaki must define what objects and activities make her happy. As Chiaki tackles Kondo’s tasks, she becomes more comfortable and confident with her neighbor. Presenting this kind of information in an emotional way works because it shows us the payoff of tackling an unpleasant task. Through Chiaki, we are encouraged to imagine how our own lives might improve by adopting Kondo’s methods.

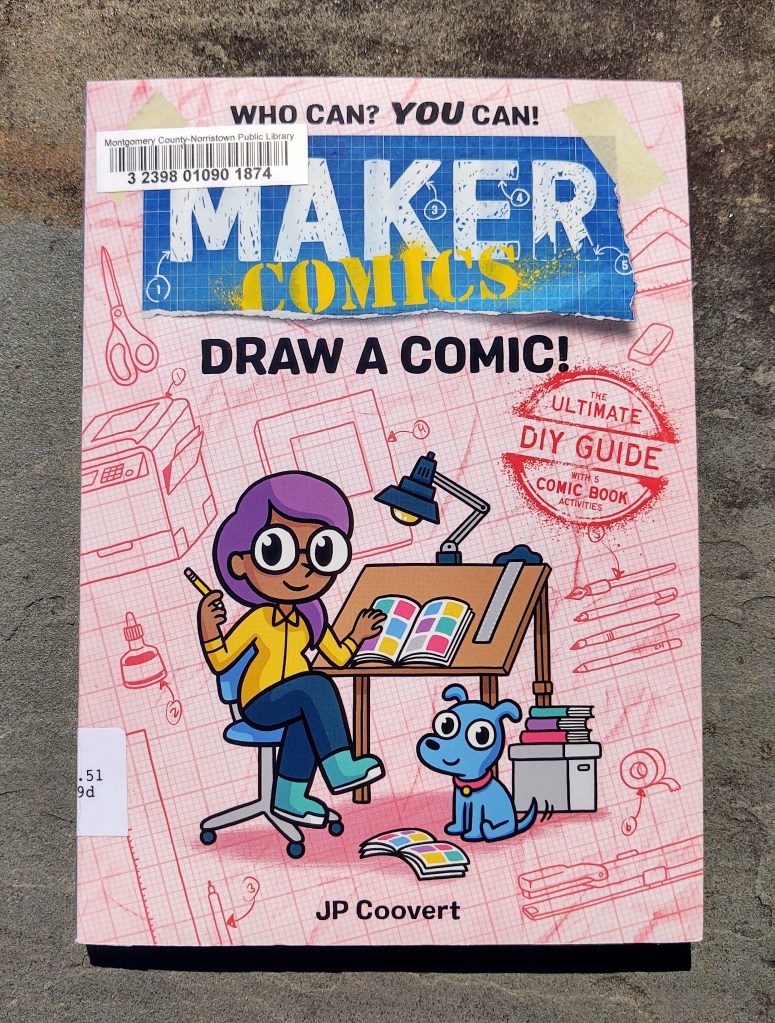

I turned to my public library to see if I could find any similar examples of instructional narratives in American comics. I was already familiar with First Second’s middle grade Maker Comics series and took this opportunity to check out their book on…well, making comics.

Like The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up, Maker Comics: Draw a Comic! embeds its guidance within a story. Unlike The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up, there is no reader stand-in. Main characters Maggie and Rex break the fourth wall to recruit the reader directly into the text, first as their assistant and then later as an ally in saving their comics library from being turned into a parking lot by the nefarious Dr. Carl Stephens.

As they pursue Dr. Carl in the following chapters, the reader is guided step-by-step through a series of projects focusing on key elements of the comics craft. These projects build on each other and become gradually more complex, with the climax of the story having the reader assemble their own comic book to unlock Maggie’s grandfather’s secret treasure.

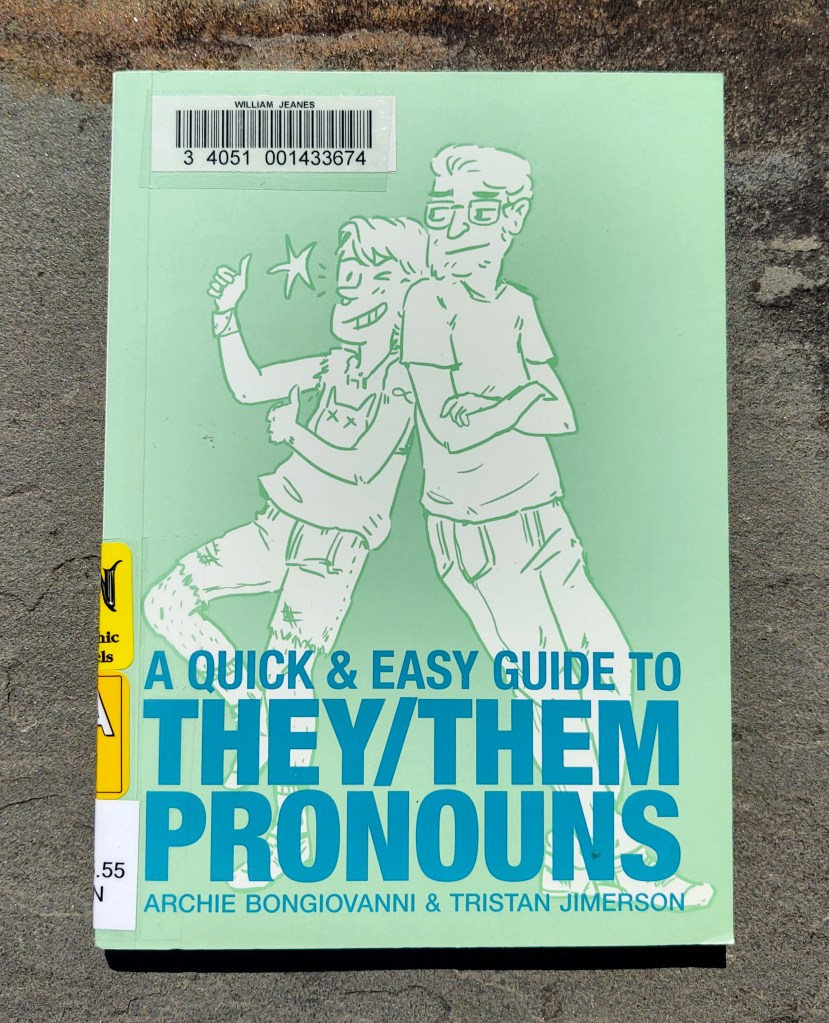

A Quick & Easy Guide to They/ Them Pronouns also breaks the fourth wall but lacks a full, continuous narrative. However, thanks to the goals of the book set out by the authors, the book manages to completely avoid the problems Makeup runs into:

[Archie]: This book exists to educate and inform people on gender neutral pronouns—specifically they/ them—so that you don’t have to do all the heavy lifting yourself.

[Tristan]: We want to keep this book short and affordable, so you can give it to friends, family, co-workers, or random people on the street.

This is quite an ambitious task, as their intended audience is broad.

[Tristan]: You might be wondering what a cisgender guy has to add to this conversation…What can I contribute to a conversation that isn’t about me?

[Archie]: If I wanted to just talk to non-binary folks, I would do it on my own. I’m a very independent person. But we’re trying to address this topic for everyone: those that have lived experience and those that are new to this whole concept.

[…]

[Archie & Tristan]: We’re teaming up to talk about pronouns from our different perspectives!

And they pull it off. Via charts, diagrams, analogies, and example scripts, Archie and Tristan manage to cram a clear introduction to pronoun usage into a 65-page book with a cover price of $7.99 USD.

After reading Makeup Is (Not) Just Magic, I thought that story might be key to delivering persuasive advice via comics. But there are various personal reasons, practical and emotional, that a reader might seek guidance on a particular topic, and quantity and depth of information can interfere with a narrative. Instructive methods are just as flexible as the comics form itself. There’s a lot of room to mess up, but also a lot of room to experiment.