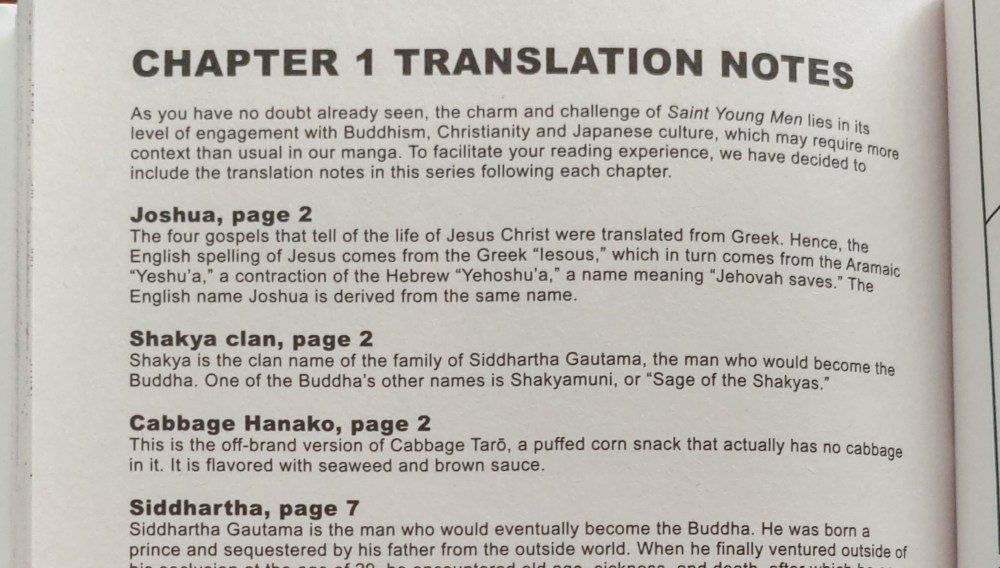

Back in December, I was gifted the brand-new, North American Saint Young Men volume 1 omnibus. The very first thing I noticed as I excitedly flipped through was that translations notes, however short, were featured after their respective chapters rather than compiled into one section in the back.

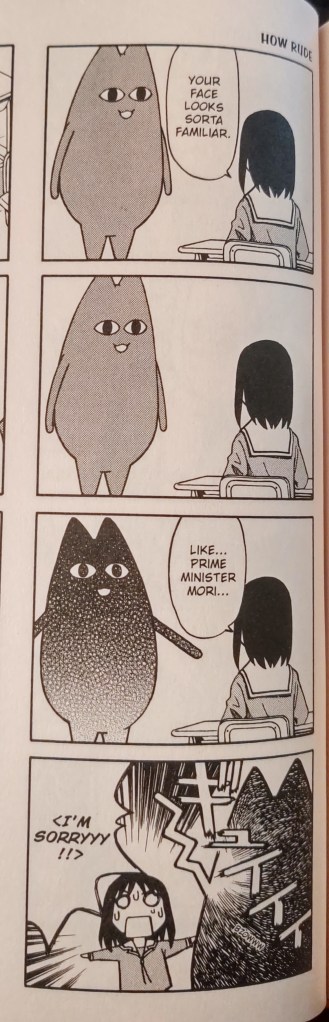

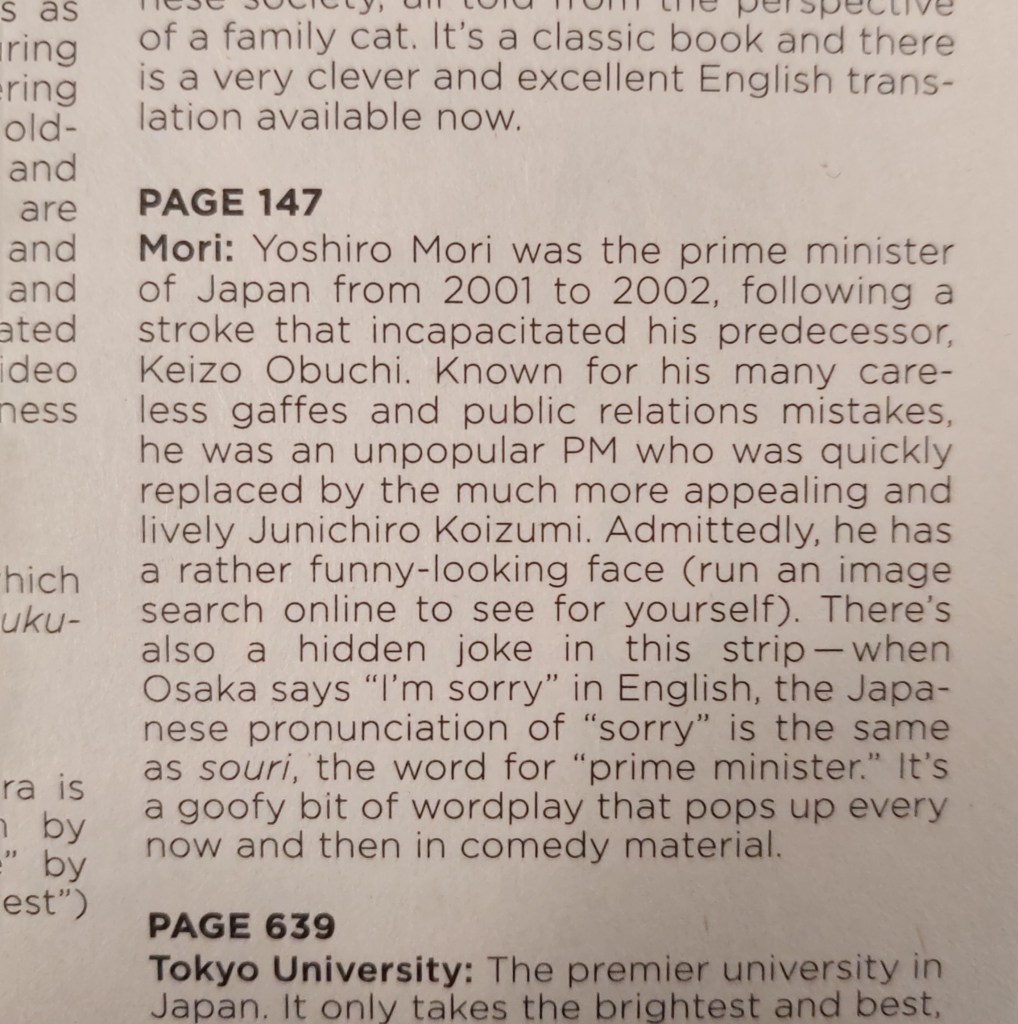

The magic of Saint Young Men‘s editorial notes was still fresh in my mind a couple weeks later when I started reading Nichijou, which made the absence of translation notes in the first volume of the latter even more shocking and devastating to me. Nichijou is a gag manga, and puns are common in Japanese gag jokes. They can also be a huge pain in the ass to localize. While it is possible to tweak and rewrite punny punchlines into something vaguely comical to English-language readers, I’m a sucker for linguistic context. For example, here’s a strip from the ever classic 4-koma Azumanga Daioh and its accompanying translation note:

My Azumanga Daioh omnibus is the 2009 Yen Press edition, but I remember seeing translation notes in the first ADV Manga editions back in 2004, albeit they might have not been much beyond explanations of honorifics and the Japanese school year. (If anyone happens have those volumes lying around, feel free to check and get back to me.) This memory got me wondering how translation notes may have developed and evolved since I first started reading manga in my teens.

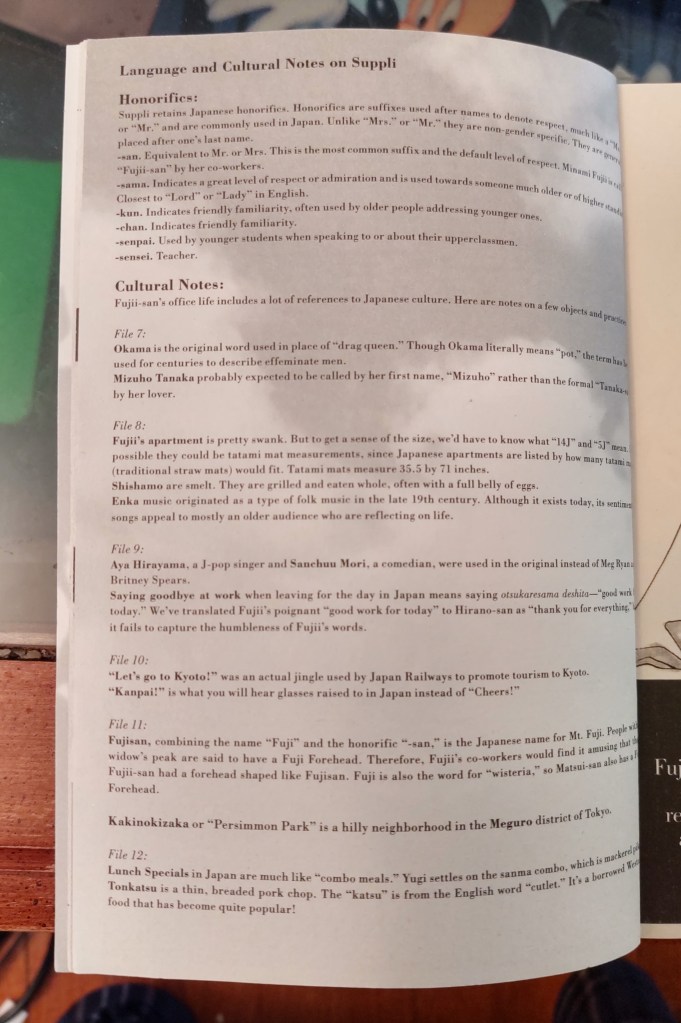

Two weeks into our ongoing quarantine, I ordered volumes 2 through 5 of Mari Okazaki’s Suppli, a josei manga first released in America by TokyoPop in 2008. (TokyoPop only made it through volume five before its 2011 shutdown, and Suppli‘s current licensing status is a tragic mystery.) Volume 2 features a page of “Cultural Notes” in the very back, between the volume 3 preview and TokyoPop ad placements. These notes cover honorifics, slang, and pop culture references. There are also a few comments on localization choices, such as the decision to translate “otsukaresama deshita” as “thank you for everything.”

The entire TokyoPop run of Matsuri Akino’s Pet Shop of Horrors happens to be sitting on my bookshelf, so I did a quick read through of volume 4 to refresh my memory and compare how its notes with Suppli’s. As I expected, they are very different. Volume 4 had no editorial notes in the back or within panels, and the few notes the series does include are directly from the author. These notes cover the cultural and biological contexts of the creatures featured in the volume rather than localization issues. Since these notes are from the author, they also contain personal anecdotes and thoughts, unlike the (usually) neutral editorial voice of translation notes.

I’ve seen Pet Shop of Horrors listed as josei, and I agree with that designation. However, it exists in a vastly different world from Suppli. For one, it’s set in 1990’s New York Chinatown. Beyond creatures rooted in East Asian mythologies, Pet Shop of Horrors contains less content that might be confusing to or lost on Western readers. But more generally, it’s an episodic supernatural horror series, and its appeal lies in atmospheric mystery. Less can effectively become more.

I’m sure individual manga publishers have their own style guides regarding translation notes, but genres also have their own need even within those guidelines. Any extra content in a 4-koma volume is probably going to be very different from that of, say, a Junji Ito hardcover omnibus. But we can explore that in depth another day.

2 Comments Add yours