As I was flipping through my manga library, I noticed that, outside of Azumanga Daioh, I wasn’t finding a lot of translation notes in the 4-koma comedy series on my bookshelf. But do we really need them today? Maybe not.

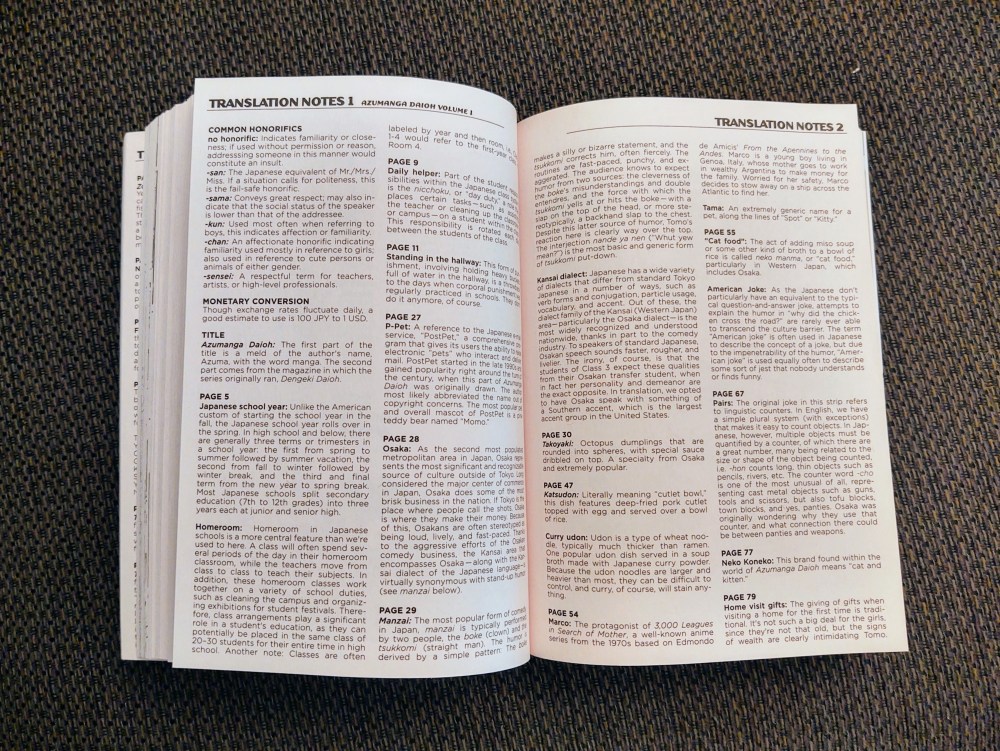

Let me begin by mentioning that although the notes in the Yen Press Azumanga Daioh omnibus are pretty thorough, it can be tricky finding editorial comments for a specific strip. Notes are located at the end of their respective original volumes, but the TOC breaks the collection up by the three years of high school covered in the series. The series run was four volumes, so the TOC chapters don’t align with the translation notes, meaning I had to physically bookmark them while reading. And even though the complete collection is published in the original right-to-left format, the translation notes are listed left to right. It’s all a bit disorienting, and probably could have benefited from the Saint Young Men treatment.

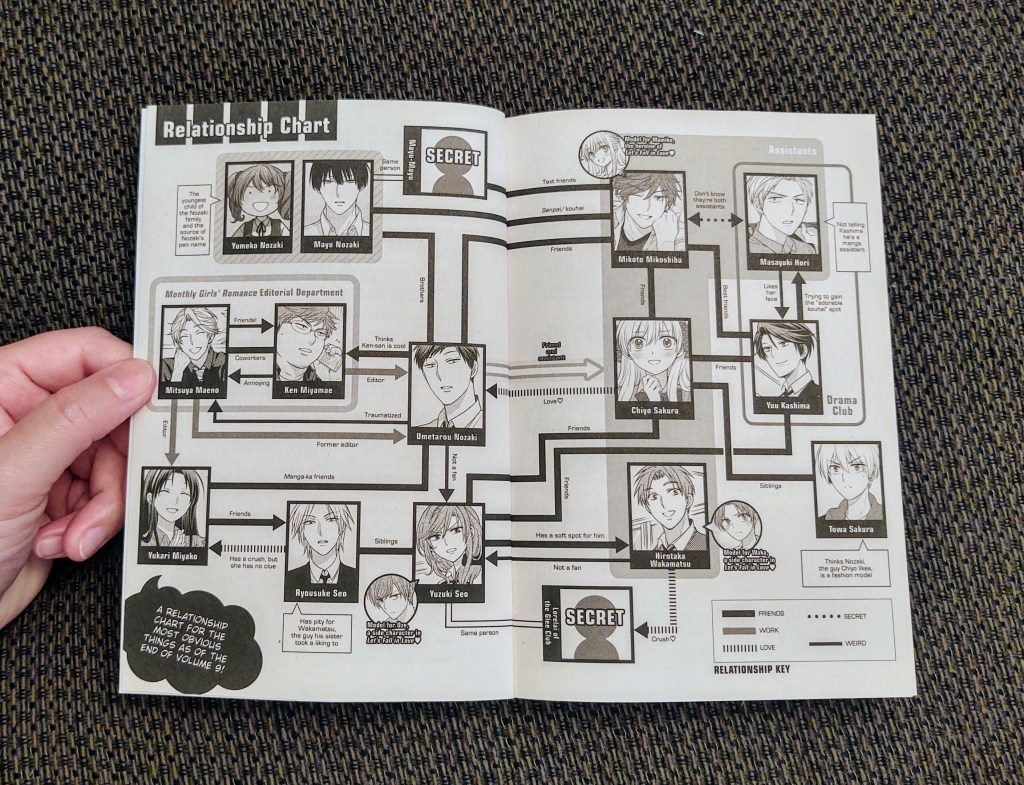

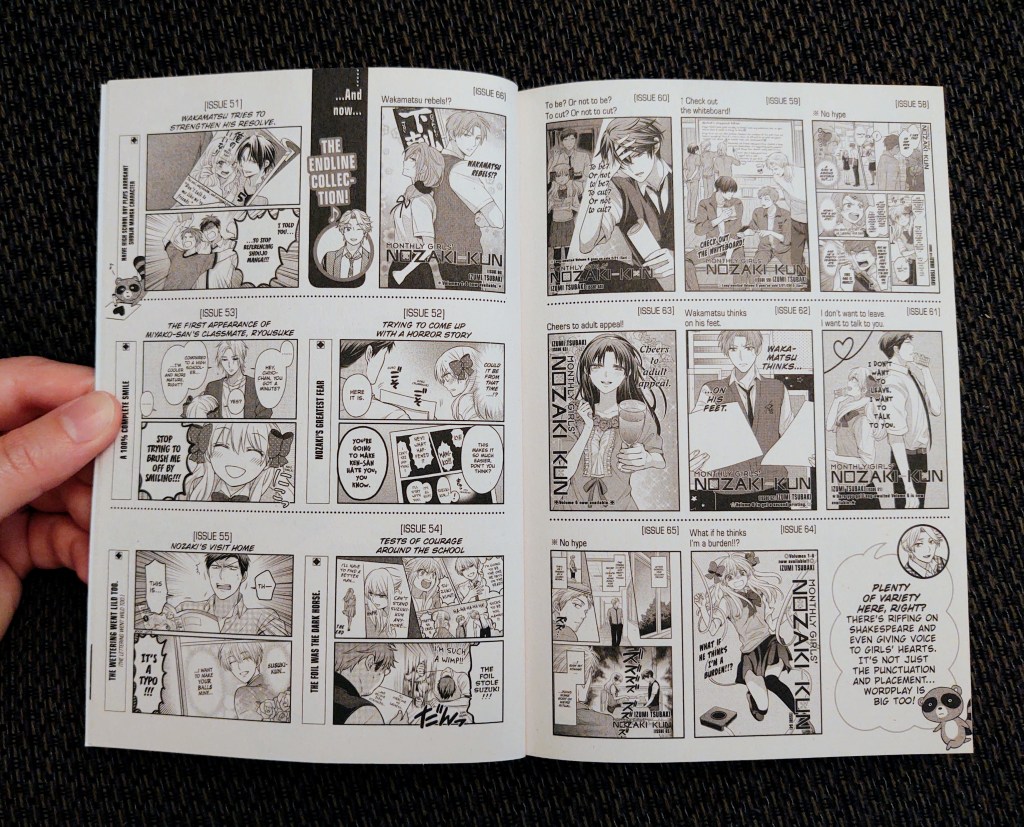

Jump ahead eight years and we have the sixth volume of Yen Press’s editions of Izumi Tsubaki’s Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun, a romantic comedy about a teenage manga-ka and his production assistants. The translation notes in the back of volume 6 are pretty sparse, and from volume 7 on Yen Press skips back notes all together. Maybe they figure any reader that has gotten this far into the series already has the necessary background knowledge. It could also have something to do with the fact that these later volumes contain other back matter.

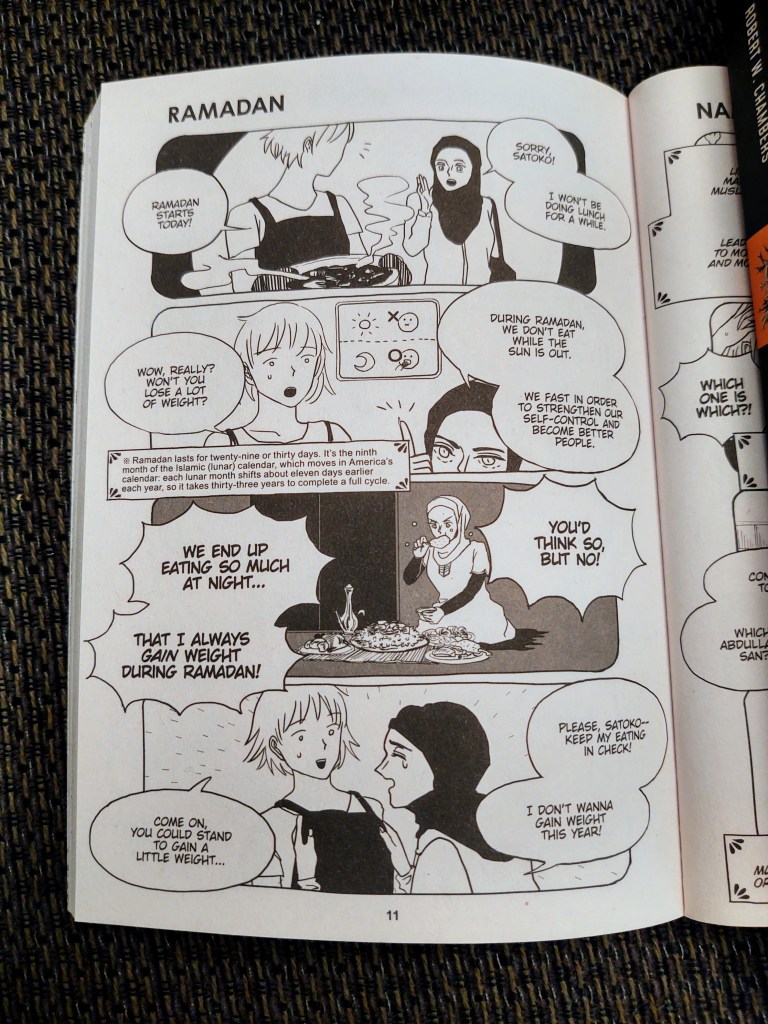

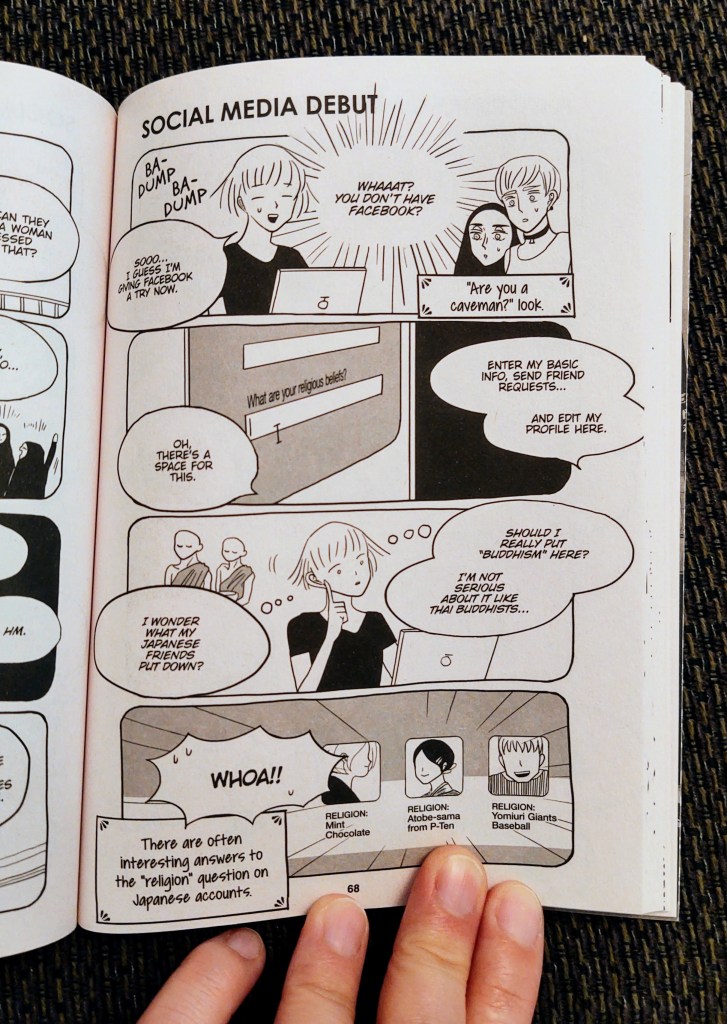

Yupechika’s Satoko and Nada from Seven Seas Entertainment is a 4-koma about two international college students — one from Japan, one from Saudi Arabia — sharing an apartment in New York. Many of its strips are more explanations of Muslim and American culture than gags, but there are occasional punchlines based their cultural discoveries and misunderstandings. There are no back translation notes, and cultural context is often included alongside the strips, usually within text boxes that were most likely in the original Japanese editions.

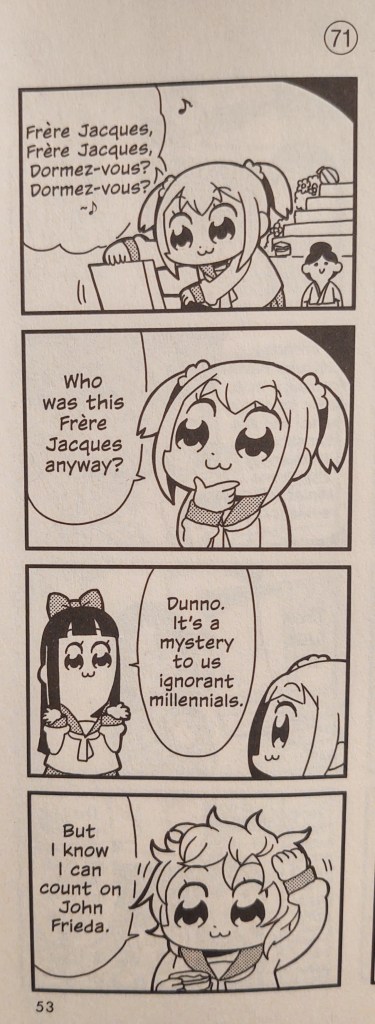

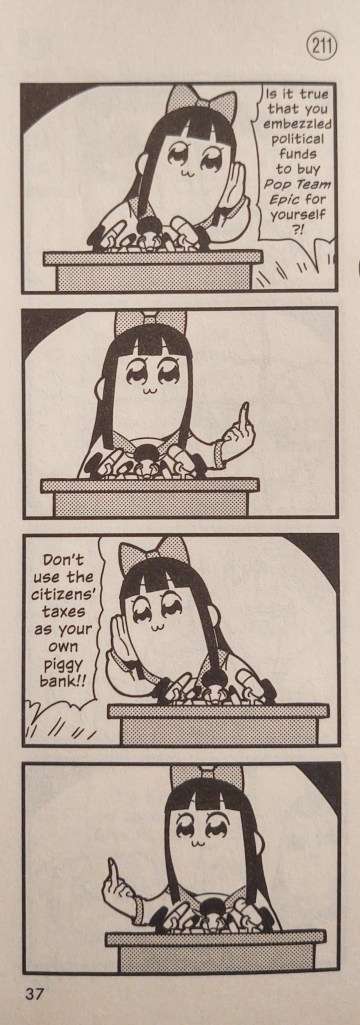

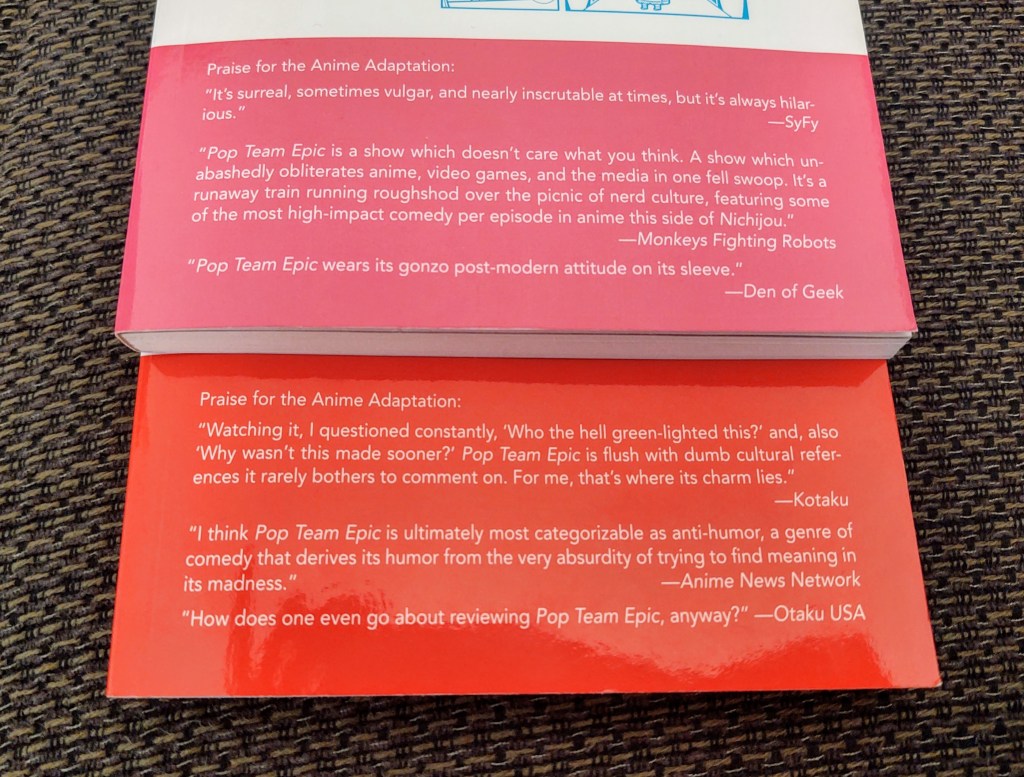

And then there’s Pop Team Epic. How does one explain Pop Team Epic? For starters, here are the blurbs Vertical Comics put on the back covers of their English editions:

Pop Team Epic’s gags are a mix of slapstick, wordplay, non sequiturs, cartoon violence, and pop culture references drawn from both Western and Japanese media and internet memes.

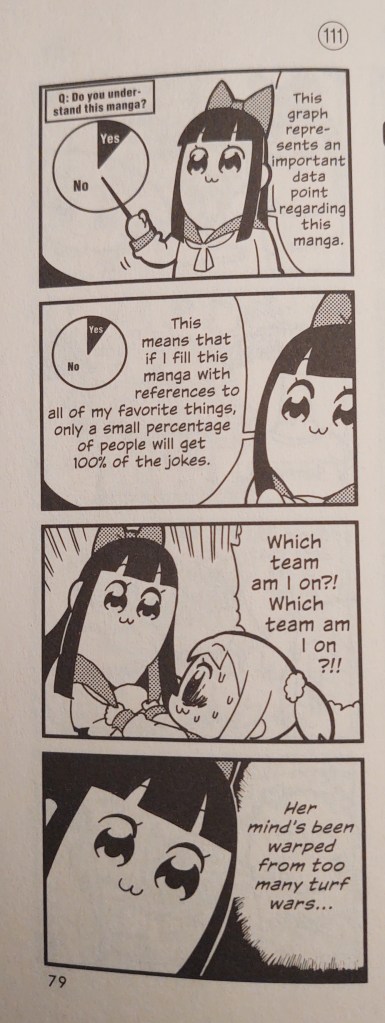

The Vertical Comics editions have no back notes, and I only found five cultural notes within the text – two explaining the comic’s publishing affiliations, two about Japanese superstitions, and one clarifying a wordplay-based punchline. But beyond that, if you aren’t, say, familiar with LINE sticker aesthetics, or don’t know what a mukbang video is, or have never heard of Salt Bae, you’re shit out of luck. Creator Bkub Okawa uses pop culture references freely and indulgently with full awareness that readers might not “get it.” And judging by the strip on the left, he’s okay with that. Vertical Comics’ eschewal of translation notes preserves Okawa’s attitude towards his audience.

Besides, many memes today come from a long line of permutations, or have evolved convergently, or are merely reflections of each other, but very rarely are we able to witness a meme’s full life cycle in real time. (Look, I am no longer ashamed about sending my advisor a Know Your Meme link to expedite an argument I was trying to make.) Comprehensive editorial notes à la Azumanga Daioh would have turned Pop Team Epic into a lecture on internet virality and culture, which defeats the entire point of, well, making a statement in four panels.

In other words, who among us hasn’t at one point quipped a line from a TV show, been met by blank stares, and said, “Oh, never mind.”